Author’s Note: I considered taking this post down, since it was written before the declaration of Covid-19 as a pandemic, before the wave of infections and death hit the East Coast or, really, even Europe or California. I don’t want the tone to sound flippant. I’m opting to leave it up for two reasons. First, to point out that health experts did KNOW things before March 11 or March 20, or whatever date someone claims now is when Things Got Really Real. Secondly, it illustrates that even when knowledge is limited, people can take intelligent steps to minimize risks. There’s no better example than that photo of Mardi Gras as an illustration of what controlling risk means.

The question was asked yesterday: What’s something you’ve longed believed to be true, but now you know is not true? When it comes to worldwide problems, we often think: It can’t happen here. I mused about this while watching the news, with story after story about the coronavirus, topped by Our Leader at a press conference emphasizing that there are only 15 U.S. cases of the virus, and really that would soon be zero. That same day, the 60th case in the U.S. was confirmed, a case which is literally Here, near-ish to where I live. At the moment, they don’t know how the person became infected, and they don’t know who she came in contact with.

It can happen here.

Americans seem to sway between attitudes of invulnerability and full-scale panic. It can’t happen to us, that’s only for exotic people in China or Iran. Next day, we’re in long lines at Home Depot asking where we can buy HAZMAT suits. I’d like to take a middle road here and discuss some fact facts about pandemics—risks, likely scenarios, treatment, and precautions.

Lessons of History

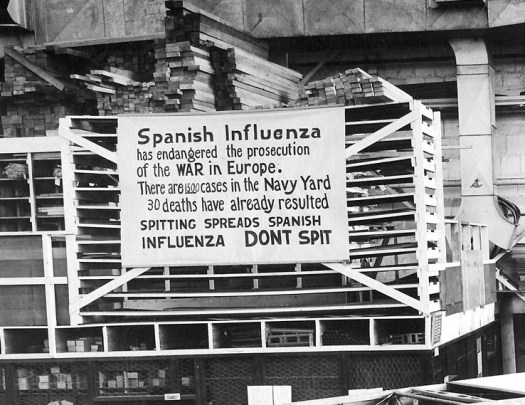

There have been pandemics before, the most prominent being the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, where 30 million people died. An estimated 500 million, 27% of the world’s population, became infected, and the death rate averaged around 2%. As many as 675,000 Americans died of the 29 million thought to have contracted the disease. The outbreaks occurred in two waves: one in the winter of 2018 during normal “cold and flu” season and a second, deadlier wave, in late summer. An unusually high number of young adults died in that second wave, unlike a typical flu. The disease hit hard even in isolated communities like the Pacific Islands and Alaska, with communities like Samoa losing 30%. In other places, such as the U.S., the mortality rate was closer to 0.5%. Not everyone was exposed. Not everyone exposed became infected. Not everyone who became infected died.

For comparison, a normal flu season in the U.S. kills between 20-40,000 people annually, about 0.1%. Like the coronavirus, the typical flu spreads when infected people cough or sneeze. People who die from the flu are usually those most vulnerable to respiratory diseases because their immune system is already compromised or they have other risk factors. Not everyone is exposed. Not everyone exposed becomes infected. Not everyone who becomes infected dies.

Continue reading “Let Facts Go Viral”