Author’s Note: I considered taking this post down, since it was written before the declaration of Covid-19 as a pandemic, before the wave of infections and death hit the East Coast or, really, even Europe or California. I don’t want the tone to sound flippant. I’m opting to leave it up for two reasons. First, to point out that health experts did KNOW things before March 11 or March 20, or whatever date someone claims now is when Things Got Really Real. Secondly, it illustrates that even when knowledge is limited, people can take intelligent steps to minimize risks. There’s no better example than that photo of Mardi Gras as an illustration of what controlling risk means.

The question was asked yesterday: What’s something you’ve longed believed to be true, but now you know is not true? When it comes to worldwide problems, we often think: It can’t happen here. I mused about this while watching the news, with story after story about the coronavirus, topped by Our Leader at a press conference emphasizing that there are only 15 U.S. cases of the virus, and really that would soon be zero. That same day, the 60th case in the U.S. was confirmed, a case which is literally Here, near-ish to where I live. At the moment, they don’t know how the person became infected, and they don’t know who she came in contact with.

It can happen here.

Americans seem to sway between attitudes of invulnerability and full-scale panic. It can’t happen to us, that’s only for exotic people in China or Iran. Next day, we’re in long lines at Home Depot asking where we can buy HAZMAT suits. I’d like to take a middle road here and discuss some fact facts about pandemics—risks, likely scenarios, treatment, and precautions.

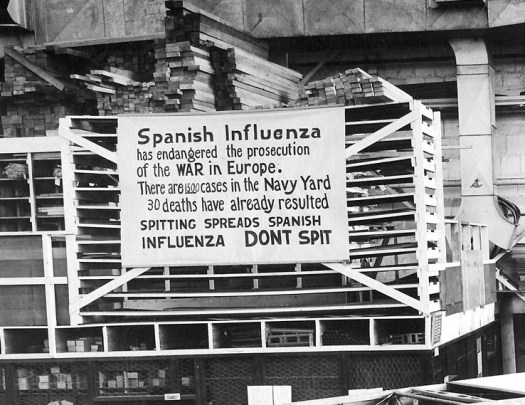

Lessons of History

There have been pandemics before, the most prominent being the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918, where 30 million people died. An estimated 500 million, 27% of the world’s population, became infected, and the death rate averaged around 2%. As many as 675,000 Americans died of the 29 million thought to have contracted the disease. The outbreaks occurred in two waves: one in the winter of 2018 during normal “cold and flu” season and a second, deadlier wave, in late summer. An unusually high number of young adults died in that second wave, unlike a typical flu. The disease hit hard even in isolated communities like the Pacific Islands and Alaska, with communities like Samoa losing 30%. In other places, such as the U.S., the mortality rate was closer to 0.5%. Not everyone was exposed. Not everyone exposed became infected. Not everyone who became infected died.

For comparison, a normal flu season in the U.S. kills between 20-40,000 people annually, about 0.1%. Like the coronavirus, the typical flu spreads when infected people cough or sneeze. People who die from the flu are usually those most vulnerable to respiratory diseases because their immune system is already compromised or they have other risk factors. Not everyone is exposed. Not everyone exposed becomes infected. Not everyone who becomes infected dies.

Why You Might Want to Be Worried

The seasonal flu numbers are always scary, but it amazes me how much people shrug off the data. People don’t get flu shots; they’re not worried because “they don’t get the flu.” On the other hand, others they come in contact with don’t always call it the flu. How many times have you been near someone in the last two months who has “the office yuck” or “that thing that’s going around”? You might have been exposed to the flu without knowing it. Remember, an estimated 90% of the New World population died when the Europeans carried a version of smallpox, to which they had become immune. Not having had a disease doesn’t prevent you from getting a strain of it.

There are two things particularly worrying about the coronavirus, compared with a seasonal flu. First, it can take up to two weeks for someone to display symptoms, leaving an infected person a long time to interact with others. Secondly, while a mortality rate of 2% sounds very low compared with a normal flu season, that number would be awfully, awfully high if infection rates are 20-50%. What’s 2% of 20% of 7 billion people? Millions of people; Spanish flu territory.

Jumbles of Numbers

The other worrying part for me is the difficulty of getting clean information. I would like to know, for example, what is the infection rate from exposure? What’s the likelihood of getting sick, if you’re infected? Is the estimated mortality rate 2% of people who got sick, 2% of those infected, or 2% of those exposed?

Fortunately for us and unfortunately for them, the passengers on the cruise ship Diamond Princess provide an interesting setting to look for some of this information. There were 3700 passengers on the ship when a person was identified as being infected. Some 700+ eventually became infected, which is around 20%. They had been in isolation in theory, but it wasn’t consistent and strict. For example, the crew wasn’t kept separate from each other, and it’s unclear what measure they were using when preparing food. At least one Japanese doctor who boarded the ship saw breeches of protocol all over the place, with crew members and health workers not using gloves and masks or taking them off, say, to use their phone.

By the time passengers were evacuated, those 700 people had been infected and at least 8 of the 90 Japanese health workers who boarded the ship also among the infected. In other words, it wasn’t so much a quarantine as a breeding ground for disease. Yet even there, a good count is difficult to obtain. For example, one news story also mentioned “700 confirmed COVID-19 cases … not counting infections discovered among passengers after they’ve gone home. “ Wait, not counting others? Well, how many are those?

Right now, we don’t entirely know what we don’t know. Places that are good about keeping track of data don’t have what they need, while places with a lot of cases (China, Iran) are not known for sharing their info with other countries. This leads to swings back and forth between panic and foolishness. There’s no evidence that wearing respiratory masks will keep you from getting infected, but masks are selling out. There’s discussions about whether to cancel the Olympics, which is five months away, but meanwhile many large gatherings of people are still taking place. We don’t seem to be able to take a middle road of caution rather than panic, today rather than later.

What to Do

Since we do have cases in the U.S. and since we do have reliable health officials whose announcements are not yet being censored politically, there are things we can do:

- Don’t Panic, even as the numbers increase. There are going to be more cases before there are fewer cases. One thing to watch is the rate of increase. China’s daily increase has started to drop even as more cases announced worldwide. Also, pay less attention to headline-grabbing scary numbers, like how many countries have cases, and more attention to what is known about total infection rates, recovery rates, mortality rates. As far as the stock market goes, the Dow today (which dropped again, yes) is now where it was last September, September 2018, and February 2018. You could argue that the stock markets were overpriced.

- Get Facts from Reliable Sources. CDC.gov is a good go-to site. They’re updating information daily and being candid about what is known and not known. Get your news from them rather than from Facebook. Always remember that the media is trying to get you to look, so their information may over-sensationalize risks (even MSNBC).

- Have a Plan. Let’s just suppose that on April 10th, you find out that someone you know does have the coronavirus, not the office yuck or the flu. What would you do if you needed to be quarantined? Do you have enough food at home? Could you work entirely from home? What social interactions would you curtail? Do you have upcoming travel plans–what would happen if you needed to cancel them? These questions shouldn’t make you panic, but rather build confidence that you can handle whatever is thrown at you. C’mon, we’re Americans! We’re strong and resilient. We can handle it!

I like to say that if you have a contingency plan, you won’t need it. Instead of choosing between ohmygod I need a mask vs. nothing to worry about here!, it might be better to just think a little about what might happen. Keep yourself accurately informed.

And wash your hands.

YEP–ALL OF THIS. The situation at UCDavis Med Ctr is quite interesting, too. The woman was moved to Davis from an “unnamed” hospital in Sacramento. Although Davis took SOME precautions as they knew the situation involved a viral infection, they obviously did not take ALL possible precautions because they have now sent a few staff members home and told them to monitor their temperatures! They requested COVID-19 testing from CDC, but they were denied for four days; however, CDC decided, OK, test her. Her results came back positive for COVID-19. And what about the front-line Health Care workers at original transferring hospital? No one knows. She arrived at Davis intubated, so whoever did that, if done without sufficient protection….yikes. And then if they went shopping, picked up kids from school, etc etc–there is no good scenario here. And if anyone (no one I know!) thinks Orange Julius will take care of us, disabuse yourself of that crazy notion right now. We are on our own, and the precautions listed above are excellent. We can’t cure it, we can’t guarantee we won’t get it, but we can sure as hell diminish the risks.

Great post!

Excellent point, which helps illustrate what I didn’t clarify as well I’d intended. We’re all probably going to be exposed unless we all jump in a bunker right this minute, and it may already be too late. Even the CDC and public health officials, as knowledgeable as they are, are going to make mistakes and overlook things. Instead of freaking out about exposure, we should think about the implications. If and when I get exposed, what should I do? Do I have a history of respiratory problems? How would I handle quarantining myself, if need be? If someone coughs on me, and I start to feel sick, where do I go to be tested? And, most importantly, what can we do to help?

Thanks for posting this. It was both interesting and informative. But it was frightening insofar as the incompetence shown by Trump and his administration in the bumbling way they are dealing with this matter and the inconsistency of the messaging and information.

I am sooo reassured that mister pence is in charge now.