Leg of mutton, but no other meat is used. Prepare water; add fat; dodder [wild licorice] as desired; salt to taste; cypress [juniper berries]; onion; samidu [semolina]; cumin; coriander; leek and garlic, mashed with kisimmu [sour cream or yogurt]. It is ready to serve.

From “Three Babylonian Recipes You Can Make Today”

This is a recipe that starts with a gravy. Boil animal fat, water, and spices together, using semolina and yogurt as thickening agents. Combine with meat. It’s a recipe that is 3,600 years old, from ancient Babylon. Hammurabi and friends knew how to eat.

According to several internet cooking references, gravy was created in France because the medieval French wrote many cookbooks that used the technique. Gravé is a word from Middle English, which for some reason is credited to the French. Of course, one of the better techniques for making gravy involves using a roux–flour browned in meat drippings–and since roux is a French word (though it’s based on the Latin russet or red/brown), then obviously the French invented gravy! Certainly, that’s what the French would tell you.

I call mutton patties on this! Are we seriously asked to believe that the 17th century French were the first to use the juices from roasted meat plus a thickener to make a sauce to pour on meat? Non! न! Nahin! Ng hai! Nyet! The Null Set!

Gravy is international and ancient. There are themes and variations, especially considering the distinctions among gravy, stock, and broth and across multiple venerable cultures. With Thanksgiving looming in the headlights, this is the perfect time to investigate gravy. Get out your cornstarch, flour, and semolina. The plot is about to thicken.

The Science of Mom’s Gravy

My mom made the world’s best gravy–chances are that your mom, grandma, or auntie did, too. (I’m sure those guys are arguing it out up in the Kitchen in the Sky). Specifically for Thanksgiving, you take the turkey out of the roasting pan and set it aside while you make the gravy. Meat should always sit anyway after cooking to let its juices reabsorb. Meanwhile, you pour off some of the drippings from the roasting pan, but put the pan on a medium-low stove. It’s a big pan; you might need two burners. You add flour, but very gently, making a paste between flour and oil, then adding turkey stock a bit at a time. The mixture will slowly come to a boil and thicken, while you stir furiously to get the lumps out, i.e. to distribute the flour as evenly as possible across the liquid. Continue until you have enough. Then add the giblets.

The roasting pan my mom used was battered beyond recognition and scorched from twenty years of making gravy on the stove. If you don’t have a 20-year-old roasting pan or don’t want to scratch up the bottom, then you can use a pot, but be sure to scrape off the brown bits from the roasting pan off first. Internationally-reknowned chef Wylie Dusfresne, who uses the same technique as my mom, says you could consider throwing some chopped onion, carrot, or garlic in the bottom of the pan for the last hour. The vegetables release a little extra water, which can help deglaze the pan for you. If you keep the chunks big enough, they’re easy to strain out later.

My mother also had no whisks, which I still find amazing, but she came from the Midwest, so… She also boiled broccoli. She made gravy with a big fork, which also doesn’t work as well for stirring. Use a whisk. Google tells me the French invented the whisk, and I don’t mind giving them credit for that.

Why does gravy work? And, why is gravy thick–why are sauces thick in general? Most sauces are a blend of water and a fat–they’re also a blend of flavors from food and spices, too, but the consistency has to do with the liquids. Fat is thick; water is not. And fat/oil and water molecules don’t mix. So how to get water to thicken? You use an emulsifier.

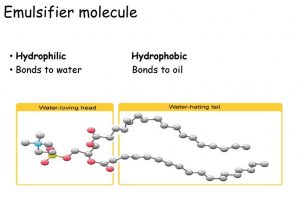

An emulsifier is something that bonds two yin/yang molecules together. Chemically, the emulsifying agent contains molecules that partly like water (hydrophilic) and partly hate water and does like oil (hydrophobic). Examples of food emulsifiers include eggs, mustard, or soy lecithin. Eggs, for example, bond oil with vinegar or lemon juice to create mayonnaise.

Naturally, I leaped to the conclusion that flour is an emulsifier but it is not. It is a thickener, but it’s not acting as an ambassador between the water and oil. Instead, the liquid that you add itself–in this example, stock–contains gelatin, which is an emulsifier. Also, the meat juices contain protein, another emulsifier, in addition to their fat. Overall, what you’re doing is using gelatin and proteins to entwine flavored water and flavored fat and thickening them with cooked flour. Yum!

Sauce: Theme and Variations

Clearly, the difference between gravy and stock is the flour and drippings from roasted meat. We could debate whether gravy is a sub-category of stock or not, but it ‘s probably more cousin than child. What’s the difference between stock and broth? Three essential things: herbs, bones, and cooking time.

Broth is made from boiling vegetables and/or meat for enough time to flavor the water. Seasoning is usually added so that the result is yummy enough to be eaten as a food unto itself. “Bone broth” is wildly popular these days for its health benefits. This is funny because “bone broth” is stock. Stock is made from boiling meat long enough for the collagen/gelatin in the bones to dissolve into the water. It’s often used to add to sauces rather than be eaten on its own, but stock brings the emulsifying collagen to the sauce party.

White gravy, as in biscuits and gravy, is milk-based rather than stock-based. But the same idea applies. The magic emulsifier here is–Ta-Da! Butter! Butter (and margarine) are already emulsions of water in oil. Basic white gravy is butter, flour, and milk plus animal drippings, such as sausage. If you take away the sausage drippings, then add shallots and nutmeg, it’s now a Bechamel and costs a lot more.

- Part of the Sauce Family Tree

- Brown (typically meat juices)

- Broth: boiled vegetables and/or meat

- Stock: boiled meat until the bones give up collagen

- Gravy: meat juices + flour/thickener + broth/stock

- White (milk)

- Gravy: butter and/or meat juices + flour/thickener + milk

- Bechamel: butter + flour/thickener + milk + shallots+ nutmeg/pepper + $$$

- Red (tomato)

- etc.

- Brown (typically meat juices)

Gravy’s International Cousins

The first person to invent gravy was likely not French, Middle English, or even Babylonian. As my wise spouse put it, paleolithic woman looked at the juices dripping off the roast mastodon and said, hmmm good…. We know that ancient humans cooked meat. In fact, one of the huge evolutionary benefits of fire (aside from warmth and scaring away predators) was that cooking meat reduced chewing time and provided more nutrition. With 10,000 years on their hands, it’s surely likely that homo erectus experimented with collecting drippings, adding pounded grains, and river water.

The 36-century-year-old Babylonian recipe was for cooked mutton with leeks and all sorts of spices, mixing the liquid with semolina and sheep fat. Gravy, in fact, pops up all around the world. It might not be called gravy, but as you look at the components and methodology, you see a similar process. Water-based liquid + thickener + emulsifier + a fat.

Moles: a mole is a sauce from Mesoamerica. Many people associate moles with chocolate, and it’s true that traces of chocolate have been found on plates from the Yucatan 2500 years old. But chocolate is only a maybe ingredient in a mole. What a mole always has is complexity. There are many ingredients, some which may be pre-roasted or cooked. Several of them, like chiles and nuts, will then be ground together, then added as a paste to a liquid, anything from water to vegetables, like tomatilloes. Add proteins and fats from a liquid like a stock or brother, cook together to thicken or emulsify, and you have a cousin to a gravy. The other important distinction to a mole is that instead of the mole enhancing the meat as European sauces do, the mole sauce is the star of the show, with the protein as the afterthought.

Brown Sauce: Chinese cuisine, like its French relative, has dozens of sauces. The typical Chinese gravy most familiar is likely a bastardized version used in takeout, often in non-Chinese cities. The standard brown sauce used in beef and broccoli or chow mein is soy sauce + cornstarch + beef or chicken stock + sesame oil. Whether it’s flavored also with garlic and/or chili paste and/or any number of spices, it will have the liquid, the thickener, the emulsifier. It might or might not be called “Chinese gravy,” but it’s in the gravy family. Some Cantonese cuisine articles even point out that mixing the paste of roasted, mashed garlic with an oil will speed up the emulsifying process, much like a butter/flour paste in a roux, and can help the completed sauce last more than a week.

Curry: the English traded with Tamil merchants in the coast of Southern India and learned the word kari, which was the word for sauce. It originally might have referred to a sauce with curry leaves, but other cultural versions of the word simply meant a mix of meat and vegetables with a sauce, like stew. Over time, some places use curry to mean a mix of spices. Each household or restaurant might create their own special blend, and there could be several blends of “curries.” But curry can also mean the sauce that goes on the meat/vegetables, which probably contains those spices, plus the liquid, oil component, and a thickener. For Indian curries, the thickener is usually not flour but rather ground nuts, cornstarch, or any paste, often made by roasting the thing and removing its water. In other words, you take the liquid out of the ingredient, grind it into a paste, then reintroduce it with spices, and add melted fat (often ghee, clarified butter) and broth. Voila! Curry! Gravé!

Get your whisks ready for melted fat, thickener, water, and flavor. Whatever you want to call it, it might just be the best part of Thanksgiving!

As usual you have done a superb job educating us on gravy. Judy’s mom made chocolate gravy which was poured over biscuits for breakfast. My mom made something called red eye gravy (or streakedy gravy if you were from East Texas) which was basically bacon grease with something stirred in to make the streaks. I don’t know what that something was, I will have to ask my sister if she knows. Hope you had a bounteous Thanksgiving.

I made some of my best gravy! Even I can teach myself something. Red gravy… eye gravy… I forgot about that one. The Internet says what your mom might have poured in there is black coffee. Hmmm…. I am intrigued….

Thanksgiving would absolutely not be the same without gravy, or grave’ — and I agree about putting in the giblets (if not in the sauce, then nevertheless, in the stuffing or dressing). White sauce is one of the first things I learned to cook. And we had it on broccoli, cauliflower, or brusselsprouts when I was a kid; loved it. I sure enjoyed your going into moles, curry, and Chinese brown… even bone “broth” (which I want to do). I’ll have to try making bechamel — so far, I’ve only ordered it from a menu. And hear-here to paleo gals! Yeah, yum. Don’t think I could go vegetarian for long.

White sauce = bechamel just add nutmeg. So you’ve made Bechamel (nutmeg-free version).